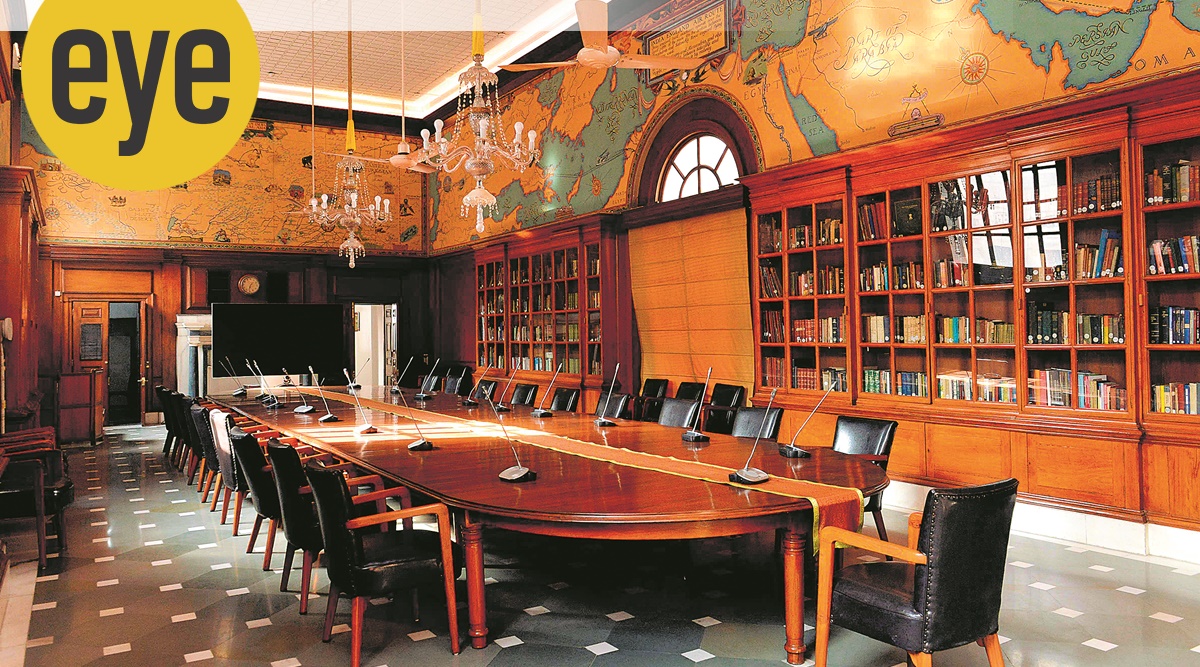

It is Tuesday and the weekly afternoon ritual in the cabinet room of the Rashtrapati Bhavan begins. Seated around a majestic rectangular hardwood table that can easily accommodate 50 people, we are gathered for a staff meeting. The agenda for the meeting is displayed on a large LCD screen placed at the far end of the table. Sometimes, the topic of discussion concerns an upcoming visit of a head of state. But, normally, the discussions are less exciting but equally important, such as administrative issues of the vast President’s estate or upkeep of the grand main building and its numerous rooms.

Fifteen minutes into the meeting, green tea and samosas are wheeled in, providing a welcome diversion. The meeting persists with the speaker oblivious to the excitement caused by the entrance of the liveried attendants. The long table soon sees a flurry of activity with the clanging of silverware and clinking of cups. As one sips tea, one marvels that this was the same table on which history had been written. Or rather, drawn up.

In 1947, the cabinet room had served as the final venue for the Radcliffe commission, set up to demarcate the boundaries between India and East and West Pakistan. At that time, large detailed maps had been laid out in the space now invaded by teacups and plates, holding leftover crumbs. Men sat down in meetings across this table agonising over a thin pencil line, whose shape decided the destiny of millions across the subcontinent. The man in the hot seat then was Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a British lawyer who had never set foot in Asia before. He was brought in by the Viceroy Lord Mountbatten to do the inglorious job of dissecting India. As the poet WH Auden wrote: “But in seven weeks it was done, the frontiers decided; A continent for better or worse divided. The next day he sailed for England, where he quickly forgot; The case, as a good lawyer must” (Partition, 1966). Sipping my tea, I hoped history and the poets would judge us, sitting here today in the same room, more kindly. Details from the maps painted on the walls of the cabinet room

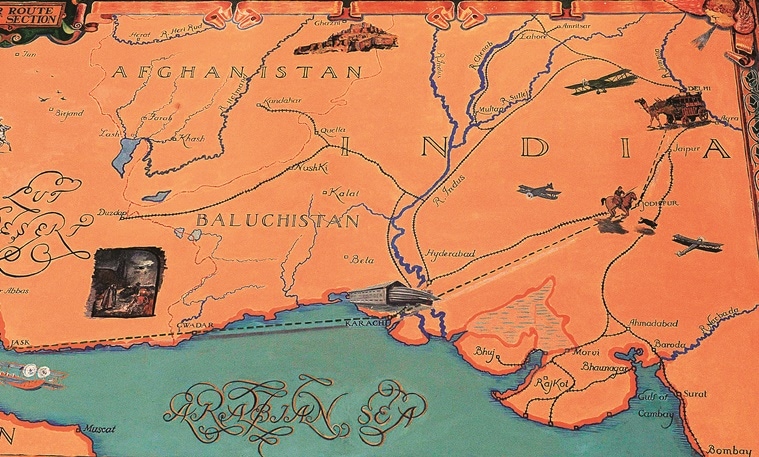

Details from the maps painted on the walls of the cabinet room

Meetings are a remarkably enduring aspect of government life. They have been taking place regularly in the cabinet room for almost a century. Previously, this room was known as the council room and had served as the meeting room for the Viceroy’s executive council, the de jure cabinet. There was rarely an Indian face then. The table in the room was the battleground across which Indians tried to wrest the governance of the country inch by inch. Gradually, more Indians were included in the council until 1946, when the interim government began to function with just the Governor-General and the Commander-in-Chief remaining British. Today, only familiar faces are seen in the room and all are assuredly Indian. Like an old warhorse that has seen its share of battles, the table rests, having witnessed the sun set over the empire.

As the discussions continue, my eyes wander to the walls of the room. And these walls are like none you would have ever seen. Large maps of the subcontinent are painted on them but not the boring kinds thrust on every schoolchild. These are painted in bright colours with playful cartoons marking out important towns and sights.

Sir Edwin Lutyens initially had planned to paint more sedate and ornate maps inspired by the Galleria delle Carte Geografiche (gallery of maps) in the Vatican, painted by geographer Ignazio Danti between 1580 and ’83. He proposed the name of MacDonald Gill from London for the job. In a letter to the Viceroy, Lutyens wrote about the British graphic designer and cartographer: ‘…had a long experience at such work and is now engaged on some of the Empire Board maps’. But MacDonald Gill sent an estimate of Rs 19,000 for the job which was a princely sum in 1930.

Meanwhile, Percy Brown, who had retired as the principal of the Government school of Art in Calcutta in 1927 and was serving as the Curator of the Victoria Memorial hall, offered to paint the room with Indian painters and craftsmen for half the price. Between June and October of 1930, the paintings on the walls of the cabinet room were brought to life by Indian painters hired by Brown, most of whom had never travelled beyond their own country. Yet, I can’t help but wonder how many dreams these walls have given wings to.

The walls continue to maintain their magical spell over me and I can’t seem to peel my eyes off them. There are magnificent sea dragons, resplendent tigers, moustachioed men peering into the horizon, alluring sea nymphs and fleets of camels. Etched on the north walls of the room is the air route from Delhi to London with halts at Gwadar, Alexandria, Athens and Belgrade. Each of these cities is represented by a charming motif. The maps don’t just reveal places, they magically transport me there. One moment you are part of a group of nomads leading their yaks across the Taklamakan and the next you are face to face with a Naga warrior in his tribal attire. Turning your gaze, you heroically escape bandits prowling above the Arabian lands to board a waiting seaplane that flies over the Sphinx. Just like that, the whole room comes alive with a kaleidoscope of lands and marvels. And you are no longer bound by the agenda of the 3 pm meeting.

Meanwhile, in another world, the meeting draws to a close. Papers are gathered and laptops shut. As the lights in the cabinet room are turned off, you wait patiently for it to be Tuesday once more.